Is coronavirus airborne? COVID-19 transmission

Currently, organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) do not believe that the novel coronavirus is airborne. However, research into its transmission routes is ongoing.

SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, is one of many coronaviruses. These can cause illness in humans and animals, and they are highly contagious.

According to the WHO, the most common symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, tiredness, and a dry cough. Learn more about the symptoms of COVID-19 here.

However, some people with the disease may not have any symptoms at all. It is essential to understand how coronavirus transmits from one person to another. This knowledge will help protect the vulnerable and limit the spread of the virus.

In this article, learn more about its potential transmission routes, including whether or not the virus is airborne.

Is SARS-CoV-2 airborne?

Researchers do not yet understand the extent to which the virus is airborne.

Virologists are still unsure about exactly how SARS-CoV-2 spreads. So far, they have been working from the knowledge they have of other coronaviruses, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

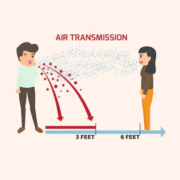

Experts tend to agree that coronaviruses are transmittable through the inhalation of droplets from a person who has the infection. Coughs and sneezes expel droplets from the body.

According to the WHO, these droplets are heavy enough that they cannot travel more than around 3 feet (1 meter). However, other research has found they can travel 23–27 feet (7–8 meters).

Airborne particles are much smaller than droplets and can linger in the air for longer. Air currents can also carry them longer distances. The measles virus, for example, can remain contagious in the air for up to 2 hours.

Airborne viruses are the most contagious. According to the WHO, SARS-CoV-2 is not airborne, but other experts seem to disagree.

How does it spread?

Most respiratory viruses are most contagious when a person has symptoms. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that the virus might also spread during the incubation period, before a person develops any symptoms.

The incubation period is the time that elapses between the virus entering the body and symptoms developing. Experts consider this to be between 2 and 14 days for SARS-CoV-2.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that the virus spreads:

between people who are within 6 feet (2 meters) of each other through respiratory droplets produced when a person with the infection coughs, sneezes, or talks when these droplets land in the mouth or nose of a person who is nearby It may also be possible for a person to contract SARS-CoV-2 by touching a surface that has contaminated droplets on it, then touching their mouth, nose, or eyes.

The WHO say that coronaviruses can remain active on certain surfaces for a few hours or several days. This varies with different conditions, such as the type of surface, the temperature, and the humidity.

How to prevent it The WHO give the following recommendations for preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2:

Wash the hands regularly and thoroughly with an alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water, for at least 20 seconds each time, to kill any particles on the hands. Stay at least 6 feet (2 meters) away from anyone who is coughing or sneezing, to prevent inhaling infected droplets.Avoid touching the eyes, nose, and mouth, as this can transfer the virus from the hands to the face.Cough or sneeze into a tissue, then dispose of it straight away. Stay at home if feeling unwell. If a person has a cough, fever, or difficulty breathing, they should seek medical attention by calling a doctor in advance. Follow state or government guidelines regarding safe working practices and staying at home. Wear a face mask in public places.

Healthcare professionals treating patients with COVID-19 are at greater risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. They should follow official guidelines for how to protect themselves, such as by wearing personal protective equipment.

The WHO advise that people only need to wear a face mask if they are treating a person with COVID-19 or if they are coughing and sneezing. Masks are only effective when a person uses and disposes of them properly.

The CDC recently issued new guidance on the use of face masks for the general population. They advise using a cloth face covering in situations where physical distancing is difficult to maintain.

People can make face masks from common household fabrics. Proper surgical masks and N95 respirators should only be in use among healthcare professionals.

For most people, it is not necessary to use gloves to prevent coming into contact with infected particles. In fact, the WHO caution that wearing gloves for too long might mean that people do not wash their hands enough, which can lead to the spread of infected particles.